The Inuit have over 40 words for snow. Some indigenous tribes have a comparable number for the color green. Depending on where we live and are raised, the world around us and the land that it is made up of informs our language. Yet, in turn, the trees have been cut down and cement has been poured over the soil beneath our feet. The land that has given us our language and our culture has been suffocated. As human action has moved farther and farther away from soil, literally and metaphorically, it has detached our words from their ‘roots’ — the Earth. Laws are written to keep people off of ‘private property,’ deeds declare who can ‘own’ land and how much, and regulations tell us where nature stops and we begin. The language that land gave us has been used to destroy land.

Tomson Highway discusses how language informs culture in his “The Place of the Indigenous Voice in the 21st Century” speech. Highway talks about the Cree language and how the rivers throughout the land created an understanding of the word ‘river’ that people in other locations would not view the same way. The Cree definition for river has a direct relation to their culture through the shared experience of the word. So how would one relate to the word ‘river’ if the rivers around them are polluted or were not accessible? We have used our language to create a culture of destruction by detaching our words from what they define.

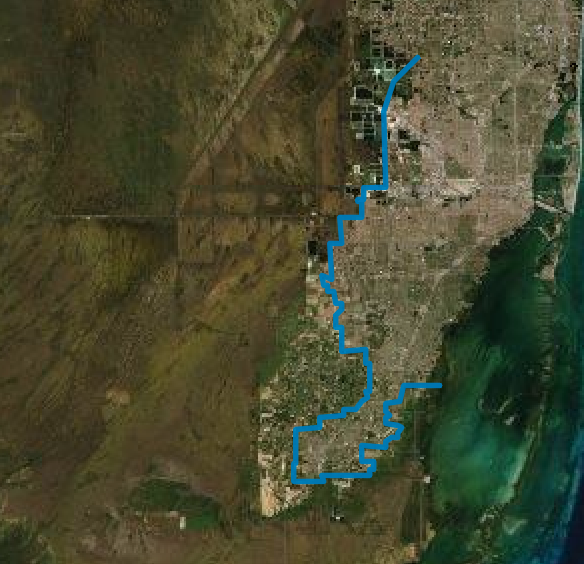

We see this in South Florida in the “Urban Development Boundary” of the Everglades. The Everglades is “the largest subtropical wilderness in the United States” and holds titles such as a World Heritage Site, International Biosphere Reserve, and a Wetland of International Importance. According to the Everglades website, this important land is protected by The Cartagena Treaty (2003) which is an international agreement on biosafety (the prevention of massive loss of biological integrity). However, the Urban Development Boundary (or UDB) exists along the edge of the Everglades as an imaginary line that serves as the boundary to where development must cease and the park begins. Despite all this protected language around the land, the UDB is continuously bending and shifting dependent on when the city of Miami is offered enough funding to do so. Legal or juridical language that is meant to protect the land is, as J.L. Austin would say, infelicitous. These words do not actively protect soil but, rather, are performative acts — they perform the idea of land protection but do not act on it.

To explore decolonizing language, we can begin sifting through these words that demarcate boundaries. In taking colonizing documents and creating poetry through the words given, we explore the possibilities that lie within the same languages. Similarly, to the poems I created from Christopher Columbus’s letters, I sift through contaminated language to find the fertile words. By digging through the colonizer’s perception of land in their words, we can extract the actual voice of the land when it has space to breathe. In other words, we remove the weeds of colonization and give land the ability to tell its own story.

In decomposing the UDB language, I found very little discussed land itself. Below is a section of it;

Words of land, soil, Everglades, etc. never appeared in their discussion of the land itself. They remove the subject from debate to further silence it. They take its agency away but not allowing it a seat at the table to speak for itself. How could we speak for land and decide its fate without ever speaking of or with land itself? Destroying and rearranging their language, I found warnings. Small poems like “some development may occur” and “expanding development through boundaries” never touch the land itself — the people who write it never touch the land, neither with their hands nor their words. They have forgotten the land that gave them the words to use — they speak languages informed by the cement offices they exist in and have lost the connection to the land that sustains them.

This is Soil. Soil is made up of dirt, minerals, compost, and earth. Soil creates the land we stand upon and in the world we live. Soil fills my apartment, in and out of pots. It gets blown from the plants by the breeze entering through the windows. No matter how I try to sweep it up and put it back, Soil chooses where and when it goes without asking permission. Soil does and does not belong to me as I do and do not belong to Soil.

Soil takes on its own agency, almost human like but without having to be compared to us to do so. Rather than detach further from soil with articles like pronouns, Soil takes its fullest form, existing in conversation with me. I begin to learn what Soil chooses to tell me the more I write about it. It informs and educates me, they speak the same language as I do. When we write on nature with nature as a subject instead of an object, nature talks back.

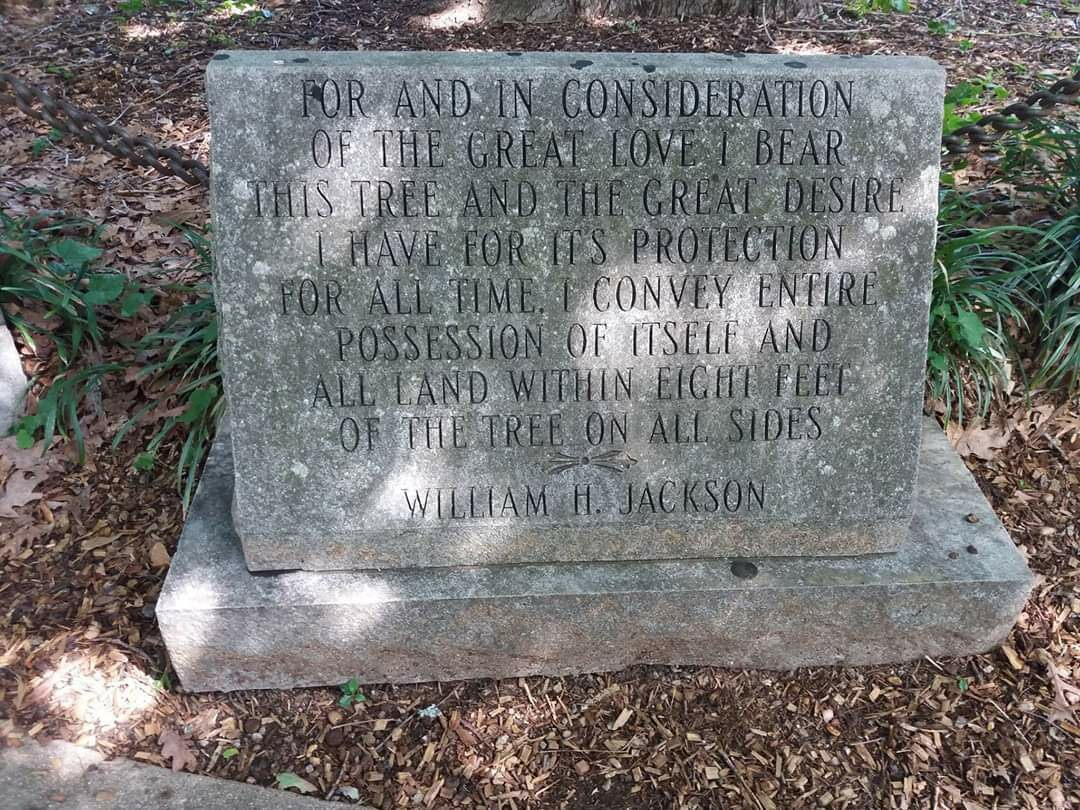

The words we use give agency back to the land. Claimed by William H. Jackson, “The Tree that Owns Itself” in Athens, Georgia is recognized as having legal ownership of itself and the land around it. The inscription below the tree reads:

“For and in consideration of the great love I bear this tree and the great desire I have for its protection for all time. I convey entire possession of itself and all land within eight feet of the tree on all sides.”

Jackson conveys possession of the tree to “itself.” He forfeits his authority over the land and relinquishes his reign — he decolonizes the tree. This action of care, of acknowledging the tree as able to hold ownership, changed the perspective of the entire city around it. The community and the tree became one, equal citizens of Athens. When the original tree fell to a storm, a seed of it was planted in its place and bears the same legal rights as its forefather — “The Son of the tree that Owns Itself” stands tall on Land it belongs to — that is, Land is the true owner of the tree, just like the rest of us. Using tree and land as subjects from Jackson’s language, I change the story that is told with the UDB statement. By bringing in nature I am able to dialogue with it. When the earth enters conversation, it speaks — one cannot simply ignore its presence as is done in the UDB by not mentioning it at all.

“This land is of/for/by itself”

“This tree is of/for/by itself”

Highway teaches us that in the Cree language there are no pronouns. Rather, things are referred to as “ana” or “anima” — a rough translation being animate or inanimate as having the presence of a soul or not. The trees and the land and the animals and the people have souls, they are ‘ana,’ while chopped wood or a hand or fur do not, they are ‘anima.’ In speaking this way, the Cree see the world differently than us. They see the earth as alive in all forms. They see the soul of soil.

This is Water. I take Water for granted as it flows out of all the pipes in my home at my will. Water sustains us, yet we waste Water. Water is limited but we think the pipes will never dry. Sometimes Water escapes the constraints of my tub and runs across the floor, being absorbed into towels and carpets. Water is unlimited while it is limited.

In Epistemologies of the South, the words “This Page is Left Intentionally Blank” appear on page 18. The blank but also not blank page comes right after Boaventura de Sousa Santos’ final line the page before that states “This is why this book, to a large extent, will remain incomplete” (17). Santos discusses multiple paradoxes that we face in our current time period: the difficulties of feeling urgency but being unable to act on it, having “only weak answers for the strong questions” we have (20). The fourth strong question asks “Is the conception of nature as separate from society, so entrenched in Western thinking, tenable in the long run?” (23). Despite nature having provided the land we are on, the food we eat, the words we use to communicate with, and the basis for our survival, we treat it as though we have evolved past the need for it. As Santos says, our society and nature are not viewed as one and the same, let alone even coexisting entities. Rather, we have created boundaries between ourselves and the soil in our words and in our actions. We pour cement over fertile land and leave the ground that isn’t covered contaminated, we set laws and regulations in place to keep important lands safe but they remain malleable in case we want to further our reign over the planet.

The detachment from the land and the self-righteousness that comes with the game of playing god also becomes the means to our own end — human life becomes unsustainable if we exploit nature to a point that there is nothing left untouched. If sustaining oneself means sustaining nature, colonizing nature and indigenous peoples is the destruction of the world that sustains us. Diana Taylor writes about what it means to be ¡presente! — to march in the streets announcing the names of the 43 desaparecidos to keep them present. In the paradox of trying to exist through colonization and capitalism, what does it mean to march in these ways on the streets that have paved over the nature that has been stolen from itself? Can we make the soil present in our concrete worlds? How can the ground be ¡presente! when we are constantly burying it deeper and deeper, farther away from us? We must bring the dirt to our bedrooms.

Throughout the pandemic, many people came to potted plants as a means of maintaining a connection with the outside world as they were stuck indoors. We did not realize how desperately we craved leaves and flowers until they were taken away from us, the boundaries we placed on nature were now placed on us. Language like stay-at-home regulations at peak pandemic times made us experience the suffocation that the earth around us is constantly facing. The earth seemed to heal as the colonizers were locked away. But what if we go beyond our potted treasures and allow the soil the same agency of space as ourselves in our homes? What happens if we become equal subjects in the space as we do when we introduce land into our conversations? Or, looking back on the UDB, do we see that our language and ideas of boundaries are all arbitrary? The soil crosses the ‘boundaries’ of my apartment, bedsheets, and bathtub with a simple breeze the same way as the UDB does not restrict the water from flooding over into developments and alligators from roaming through gardens.

As I spread the soil across my floor and feel it between my toes, I bring myself back to nature the way I bring nature to me with my words. The space I mistakenly perceive to be mine through histories of colonization ceases to hold any boundaries. I plant seeds in the soil of my living room. I water them and walk among them. The soil and I lay in bed together. We speak to one another and it cares for me as I care for it. I do not wash it off because it cannot wash us off. I experience my world as if it were ‘contaminated’ in the way we have contaminated it. I allow the dirt to spread past the boundaries of the tarp I have laid down for it and into my hallway and my sheets. I learn to live in it.

By covering our floors with soil, we create a new generation of earth as the “son of the tree that owns itself” does. We ‘cover-up’ colonization by burying it below the soil that it tries to contain below. We expose the cracks and crevices where trees and grass can grow out from our floorboards and sidewalks. We plant seeds in this new earth and let it grow before us, we make room for it in spaces we assume to be ours. We open the windows so the soil and the birds can exist among us. We give the earth back itself. We keep marching over and over again perhaps to eventually dig ruts in the pavement and have our feet back in the soil that’s suffocated under it. In moving from the UDB to The Tree that Owns Itself, Cree and soil in the bedroom, my intent is to show how we can decolonize land and soil by decolonizing language itself. As I sift through words that suffocate the soil, I create room for the soil underneath to breathe and come to the surface once again. To find the solutions to our strong questions and to return the land to itself we must rearrange our words until we can hear the land speaking back to us. We decolonize the language the land has given us by giving land back to it. We may walk in dirt, we may seem to not move forward, our words may be lost and mistranslated, but it is in these practices that we begin to uncover the cover-ups.

This is Language. It was given to us by Land. I use it to give back Land.

Highway, Tomson. “The Place of the Indigenous Voice in the 21st Century.” Hemispheric Institute, 2014.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. Epistemologies of the South: Justice against Epistemicide. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Taylor, Diana. 2020. ¡Presente!: The Politics of Presence (Dissident Acts). Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books.

Atlas Obscura. https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/tree-owns-itself

Miami Dade County Open Data Hub. https://gis-mdc.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/urban-development-boundary?geometry=-83.923%2C24.826%2C-76.902%2C26.558