My main goal is to consider different methodologies as a return to Soil through performance and affect. Inspired by Ana Mendieta’s Siluetas, I would like to explore Soil as a sacred source of life where I can also bury past Eurocentrisms. Therefore, I want to reconnect with Taíno/Boricua and Lenape spiritual practices to devise a way of “cleansing” Eurocentric epistemologies from the body represented here through my silhouette over Soil, which includes documenting my own relation to a contested Caribbean indigeneity (following Sherina Feliciano-Santos’s recent work), to reinscribe the materiality of Land and Sea (following Tiffany King’s The Black Shoals) as a site for Black, Indigenous, and/or Queer resistance and decoloniality.

Geology is a mechanism of power and statecraft that has a lower resolution or a more subterranean subjective operation than more performative biopolitics, but it nonetheless continues to be repressive in its extractive qualities and sediments the settler-colonial state. This extractive praxis sets up an instrumental relation to land, ecology, and people.

Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None

The land is the finest for cultivation that I ever in my life set food upon, and it also abounds in trees of every description.

Henry Hudson (1609)

1.

I would like to speak of Soil knowing Soil is present. That I write over Soil to whom I do not belong—I belong to Soil in Borikén, Northeast Caribbean, flanked by the deepest trench in the Atlantic to the North, and by the vexed stage of empire and liberation to the South. The patch of vibrant green light I belong to has been revered and cherished by generations of colonial survivors—the poor farmers in the mountains, the isolated Black populations across the island, the descendants of Taínos who kept their kinship to Soil alive despite genocide and demographic erasure. From colonial Spanish to colonial American sugar, tobacco, and coffee economies, Soil in Puerto Rico has sustained excessive monoculture and has served as an experimental playground, as a source for racialized bodies and complex ecosystems, as a pawn to yet another colonial game.

Soil in Puerto Rico is an experimental topography—where Agent Orange and other herbicides were tested out for for military purposes, on Soil in El Yunque (otherwise designated as Luquillo Experimental Forest), whom Taínos held to be the most spiritual and important. And now, Soil in Puerto Rico once again trembles under the specter of massive re-zoning—something so familiar, so solid and material, to Soil in NYC. I would like to address Soil and say that I am listening, that we are listening, that we still have time. We will make time.

This past September, with most islanders under strict quarantine measures, the Puerto Rico Planning Board [Junta de Planificación, JP] published the Joint Regulation for the Evaluation and Expedition of Permits Related to Development, Land Use, and Business Operations (2020) [Reglamento Conjunto para la Evaluación y Expedición de Permisos Relacionados al Desarrollo, Uso de Terrenos y Operación de Negocios 2020, RC20), a near 1000-page brick in twelve volumes that would update the previous RC from 2010 and that re-defines land use on the island for private and public interests. JP offered Boricuas only thirty days to read the tome and comment the document before public hearings (virtual and in-person) described across the board as overhasty and disorganized.

Multiple sectors—agronomists, architects, environmentalists, developers, mayors, contractors, among others—resoundingly rejected the plan that would mean a complete re-zoning overhaul. Ciudadanos del Karso president Abel Vale warned that RC20 would re-define land use classifications throughout the island—without supplying scientific justification nor analyses.

Abel added that the new regulations could open the floodgates for ecologically harmful development schemes: tourism and residencies could be developed in forests and on beaches and public grounds, including thousands of hotel rooms in the Northeastern Ecological Corridor and a hotel on Isla Verde’s public beaches—directly across from Luis Muñoz Marín International Airport. Thousands of arable acres of land could be re-zoned for private (and nepotic) interests.

JP president María Gordillo stated that RC20’s main objectives centered on creating an “integrated and uniform” permit system that streamlined the long-known glacial pace of acquiring legal permissions for economic, agricultural, or commercial uses of land and buildings. Economist and urban planner Luis García Pelatti retorts that this “single permit” process is unrealistic and incognizant of the permit-approval process, conflating construction, use, operation, health, and fire safety permits in one clumsy swoop.

Any functioning administrative authority has a Land Use Plan to police what human activities occur on which grounds to better protect the environment and keep Soil healthy. This avoids building condominiums on sandy beaches or cemeteries over baseball fields, for example. Citizens of all sectors should also have (more of) a say in the process to prevent overlaps between residential, recreational, commercial, industrial, and agricultural areas—as proposed in many sections of RC20, which already prompted multiple lawsuits.

Furthermore, climate change was a hot topic before the elections—especially three years after hurricanes Irma and María, earthquakes, and multiple beach erosion headlines. When asked about RC20, all six candidates bidding for Governor vowed to veto any government plan hastily approved and disavowed by the scientific community that also presented a danger for lands of high agricultural and ecologic value.

As it seems, everyone spoke for Soil as if Soil could not hear nor respond to what they had to say.

2.

Soil quakes in fear under our feet.

Government officials argue over Soil’s economic and agricultural value, parceling Soil into plots and numbers. Economists, geologists, and statists in general determine that Boricua Soil has intrinsic economic value—and on occasion should be protected from the State itself. That said, in speaking of Soil and Land as historic patrimony, Earth is still framed for the future of the colonial nation-state—and not for corporatist immediacy, supposedly.

In its defense of Soil, the body politic talks above and about Soil as if Soil were not a living agent with a subjectivity beyond personhood. They speak as if Soil, upon whom they stand, could not perceive their intent. As if Soil were mute and unvengeful at the hand of Man upon their body.

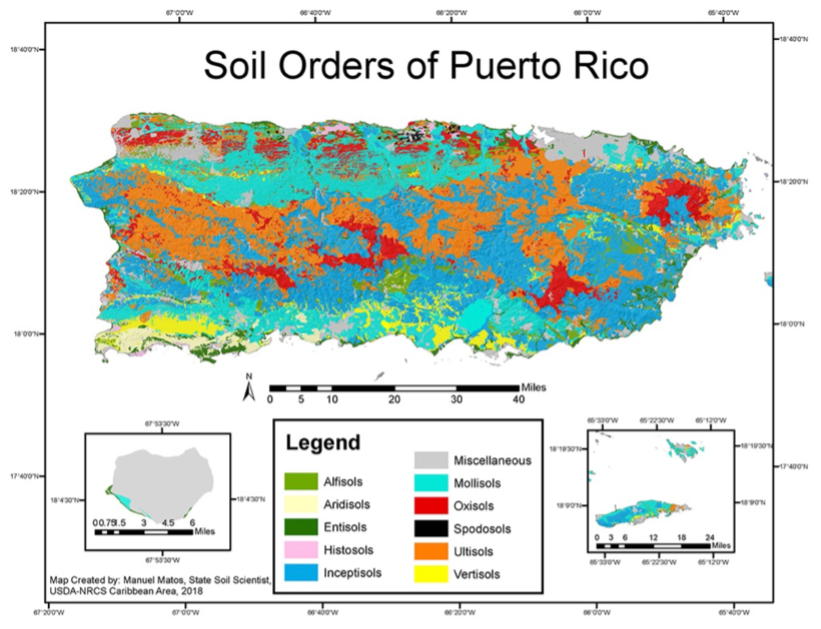

Land Use Classifications re-shape topography through geologics of classification and administration—to survey and stratify is to divide and conquer. Blessed with a tropical climate and a submarine volcanic origin, Soil breaks the surface at 18.2 degrees N, 66.5 degrees W, with dense forests, rich river valleys, mangroves and estuaries, and clays of all colors. In fact, the Boricua archipelago—barely 3515 square miles—boasts 10 of the 12 orders of Soil found on Earth, attesting to its diversity and richness.

In my grandmother’s backyard, Soil gave my family lemons, grapefruits, bananas, throughout my life. In contrast, JP appoints Soil at our family’s home for Miscellaneous use. Panoptic surveyors and city planners carve Soil’s body with numbers, black and white lines, line graphs, productivity measurements, risk assessments.

Soil feels the weight of our words and numbers. Though RC20 does not aim to re-define Soil ontologically, focusing more on territories and use, JP plans to diversify the use of the territory mapped and parceled out, to bring new use to Soil from the surface downward. In the process, agriculture and ecology—what could be the symbiosis between humans and Soil, flora and fauna, for balancing out survival along the seasons—are commodified away into Westernized futurity.

Under federal, state, and municipal jurisdictions, Soil shivers under the topographers’ pens and lines. For generations, island Soil has been a pawn for international neoliberal financial institutions and Wall Street bankers. Soil has been dismembered, dehumanized, and devalued to the point where many Boricuas leave, and colonial settlers, with no relationship to Soil, gobble up the cheapest parcels.

3.

The colonial origins of this gaze, these lines over Soil’s body, these numbers over paper that turn Soil into land for use—and not for relation, kinship, symbiosis—also shadows over human subjects, turning Bodies into flesh through Genocide, Slavery, Extraction. In A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, Kathryn Yusoff states that the “organization and categorization of matter enact racialization”. The geologic gaze that re-zones, surveys, maps, appraises, also defines, through scientific discourse, what matter is human and not. Geologists, surveyors, topographers, appraisers, as they perform their own agency (in the name of their professions) to name and categorize, enact subjecthood and distribute objecthood.

The geologic gaze forebodes economic surplus and wills extraction from minerals and flesh—Gold and Blackness, Soil and chattel. White Geology traces red and black lines on Land, rendering Soil inhuman and Bodies extractible matter:

It is the grammar of geology—the inhuman—that establishes the stability of the object of property for extraction. The process of geologic materialization in the making of matter as value is transferred onto subjects and transmutates those subjects through a material and color economy that is organized ontologically different from the human (who is accorded agency in the pursuits of rights, freedom, and property).

The inhuman—a site where the bodies of Soil, Blackness, and Indigeneity meet—classified as “inert, ahistorical, nonpolitical, inorganic”, falls in the end under a biopolitial ordering of matter, a geologic division of the spheres of politics and agency. In other words, geology operates as “a category and praxis of dispossession”.

JP—and everyone else, for that matter—barter Soil for national, statist, corporatist economic interests. That is their true motivation. Climate change arguments seem almost rhetorical. There is no intent for reckoning with centuries of abstract and material violence on Soil’s body, no attempt at really listening to Soil, at restoring any of Soil’s agency. From one colonial administration to the other, under three constitutional bodies simultaneously, Soil begs for mercy:

The inscription of geologic principles in the founding narrative of the colonial state, in terms of the colonization of both resources and racialized belonging, encodes the brutal calculative logic of inhuman materiality as praxis for dispossession that only later acquires its ideological forms, such as ‘Manifest Destiny’.

Does Soil have anything to say about all of this? The question is insulting. There is a reason Rivers resist canalization, Quarries implode after excessive detonation, and Mountains buckle after centuries of mining. Does our humanity depend on their transparency, on the gaping maw of that infinite stairwell down towards its cache of riches?

Soil would say so.

In Cannibal Metaphysics, Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s concept of American perspectivism reckons with geologic colonial modes of ontology and political representation. Through perspectivism, we can understand that all major entities throughout Abya Yalla—Rivers, Mountains, Trees, Forests, Rocks, Soil—have agency in their own way, and are human in their own way. Us “human” humans need to (restore our ability to) tune into their language, to translate their humanity to ours, to reckon with their history and strive for a new political praxis that integrates all human entities on Earth.

Can Soil speak? Of course they can. Can we hear what Soil has to say? That depends on each of us. After all, Soil sets the stage for our spectacles, becomes the beginnings and ends of our states, one of so many dwindling natural resources wrecked by the color line.

After centuries of environmental racism and capitalist extraction in the Caribbean, what does it mean to want a realer relation with Soil? How can we help Soil to heal? Even when we are in a diaspora far, far away?

4.

Coloniality meshes Soil and Black and Indigenous bodies in a regimen of extraction and hypervisibility. The union of Soil and Body, however, holds political and aesthetic potential for an exercise in decoloniality. I asked myself, how could I even begin re-orient my Body towards Soil?

I am drawn to Ana Mendieta’s Siluetas for her intent to return to Soil through solitary performative and artistic practices informed by Afro-diasporic and Indigenous cosmologies. She ventures forth into the wilderness (in Iowa, on the US-Mexico border, in Cuba) to enter in communion with Soil, to speak with and listen to, re-framing both their respective agencies mediated by uniting both their Bodies throughout these Siluetas.

By tracing her silhouette onto Soil using natural elements and audiovisual documentation, Mendieta’s body landscapes her return to Soil through performance art—a material and conceptual exercise in decoloniality and abstract representation.

Born in Cuba and exiled with her sister early in the Revolution to various orphanages in Iowa and the Midwest, Mendieta’s artistic practices take place out on Soil’s body, terraforming her figure into and onto Earth. Whether wrapping herself in black-inked wraps like Ixchell Negro or framing Miami Beach waves in Ochún, Mendieta’s Siluetas underscore a respectful and care-full search for kinship with premodern spiritual practices in the greater Caribbean basin. She speaks with Trees, with Rivers, with Soil, as she offers her flesh to Art.

Mendieta activates a relation with Soil mediated through the landscape and the female body. Her silhouette performs an indissolubility between her Body and Nature to the extent that she too is organic matter extracted from Soil; as a natural element, she finds her origins in Soil, in the material earth. This way, both Bodies escape essentialisms: this represents a return to a Soil before Modern Man traced his lines on the ground.

Mendieta’s female Body mediates between natural elements and the traces of human presence: both figures enter the aesthetic to underscore a shared material reality of forced transparency and extraction.

In Tree of Life, Mendieta covers herself in wet, viscous Soil, Mud, and nearly camouflages into the bark. The irrefutably human form translates Soil’s agency to our (visual) terms as well as links her Body to Trees. Where does the Human end, where does Soil start to separate from Trees? Our geologic gaze halts in its incapacity to name the inhuman here muddled:

The discipline of geology is intrinsic to this structural inscription of subjects into matter-objects or property. Compartmentalization and categorization of matter produce the fungibility of the slave as ‘thing’ and the grammar of ‘thingification’.

In other words, the words with which we categorize Soil and Bodies, the sites in and through which we live and expand, furnish the geologics that thingify Black and Indigenous populations, inscribing capital and material extractability in their Bodies-cum-flesh. Inhuman geologics perform subject positions (the I who measures, names, surveys) by dividing matter into human and inhuman—the condition for objectification and the violence of extraction, resting agency from Soil as well as Black and Indigenous populations.

By disappearing her flesh, Mendieta’s silhouette performs on Soil’s body a naturalized association between the female body and extractible organic matter with surplus economic value. What does Soil seem to say through her? Both Soil and Woman here resist and defend, arms raised, directly confrontational, against Man’s geologic forces.

Unable to divide and conquer, our gaze is forced to change perspective. These silhouettes return agency to Soil and restore through abstraction the forms with which spectators can link Soil with Human on a material level. Soil-cum-flesh becomes Human Body, the materialization of an absent presence, and performs a metamorphosis: the human history of Soil is brought to the surface. There is power and solidarity in this act, there is an intent to reckon through (a return to) matter the toll of the past in the present.

5.

Viveiros de Castro says that belonging to Land, as opposed to being Land’s proprietors, is what defines the indigenous experience. I interpret some of Mendieta’s Siluetas as personal-communal attempts at relating through kinship with Soil, at broaching a long-contested link towards Caribbean indigeneity. Loosely, the Siluetas can be interpreted as a decolonial exercise in restoring a suggestive, inclusive ancestral indigeneity that she returns to repeatedly in her Siluetas and other sculptures (like her Esculturas Rupestres). She was not Taína nor any other type of indigenous Caribbean, neither was she Maya nor Santera—but their gods and legends inform her artistic practice. My claim is that Mendieta’s Siluetas affirmed how, despite her life in exile, her Body truly belonged to Soil, in various topographies and through varied manifestations. What can we learn from her attempts at reaching or returning to Soil?

In A Contested Caribbean Indigeneity: Language, Socail Practice, and Identity Within Puerto Rican Taíno Activism, Sherina Feliciano-Santos emphasizes that contemporary national narratives rely on the myth of Taíno extinction to espouse settler futurity through cultural nationalism. Because Taínos (and other indigenous groups) were “entirely exterminated” during the early decades of the American Conquest, contemporary Caribbean folk (like Cubans and Boricuas) can lay no claim to any form of Indigeneity. Taíno/Boricua activist groups are vilified for being anachronistic at best and fraudulent at worst. Having to prove exactly how Indigenous you are, whether discursively or genetically, or to justify their relevance in the national present, is not a new phenomenon for Indidenous peoples across Abya Yalla.

Puerto Rican cultural nationalism, for example, “developed in response to US efforts to establish cultural dominance, romanticized the Taíno as a national legacy”. Are Taíno gods, stories, and lives solidly in the past? Their petroglyphs still scream mutely onto a deaf forest. What of the Taínos and Boricuas whose bodies form part of Soil—when will we finally listen to (all of) them? If the Taínos that truly belonged to Soil are gone, supposedly, locked in the colonial past, and we Boricuas are being cast out of our homes through climate change and financial terrorism, if our primordial relations to Soil are all but severed, how can we return home and build a future for ourselves?

Similarly, are any attempts at restoring any form of centripetal Caribbean Indigeneity doomed to the failure of anachrony?

Leanne Betasamosake Simpson might affirm that I am guilty of falling into autogenocidal tendencies. Though they tie the term to how contemporary indigenous communities impose heteronormative gender binaries and compulsory heterosexualism as a self-policing colonial dogma that denies Two-Spiritedness, I relate autogenocide to Feliciano-Santos’s formulation of Caribbean Indigeneity as always already disavowed, culturally and historically, both from within and from without.

Even begging the question—are we (or can we) be Taíno?—is a practice in autogenocide, a collective extermination of my own ancestral kinship to Soil and to our Boricua ancestors, a denial of a future in which Taíno Soil has a voice through my Body, through my art.

I pray the artist present might have agreed with me.

6.

All these matters frame my art piece as an attempt to decolonize my own artistic and academic practices. To re-orient my body towards Soil, I must first reckon with where I now sit and write—Bushwick, Brooklyn—ancestral lands previously inhabited by the Lenape of Lenapehoking. Dispersed across five federally defined nations in Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Ontario, both Taínos and Lenapes were shipped across Land and Sea, severed from where Soil fed, clothed, and raised them. To unite both diasporas, from water to earth, I shall trace my silhouette—arms raised in defense and contention—with seashells. My aim is to document the progression of the shadow of my body on Soil in my backyard, functioning as a natural archive for other aesthetic experiments—like sacrificing sections of RC20 (those that transform parts of the island into abstract sections and geologic denominations) by crucifying them with Taíno iconography and burying it within this silhouette, among other actions.

References

Alvarado León, Gerardo E. “Parca La Presidenta de La Junta de Planificación Sobre Críticas al Reglamento Conjunto 2020.” El Nuevo Día, 1 Oct. 2020, p. n.d.

Alvarado León, Gerardo E. “Entidades Advierten Sobre Posible Impacto Ambiental Si Se Aprueba El Reglamento Conjunto 2020 de La Junta de Planificación.” El Nuevo Día, 25 Sept. 2020, p. n.d.

Feliciano-Santos, Sherina. A Contested Caribbean Indigeneity: Language, Social Practice, and Identity within Puerto Rico Taíno Activism. Rutgers U. Press, 2021.

García Pelatti, Luis. “NULO EL REGLAMENTO CONJUNTO A LOS 100 DÍAS.” Sin Comillas, 13 Apr. 2021, https://sincomillas.com/nulo-el-reglamento-conjunto-a-los-100-dias/?fbclid=IwAR2uu36ZR0ziT1lZKf8EX0-fYffHbmpUt_divOsURf5KTe7t6wJOLjN4q9Q.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. “Queer Indigenous Normativity.” As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance, U. of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. Caderno n.65: Os Involuntários Da Pátria. Chão da Feira, 2017, https://chaodafeira.com/catalogo/caderno65/.

Wood, Tania E., and Grizelle González. WhendeeL. Silver, SashaC. Reed, MollyA. Cavaleri, “On the Shoulders of Giants: Continuing the Legacy of Large-Scale Ecosystem Manipulation Experiments in Puerto Rico.” Forests, vol. 10, no. 210, 2019, pp. 1-18.

New York City Soil Survey Staff. New York City Reconnaissance Soil Survey. United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2005.

Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. U. of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. “Queer Indigenous Normativity.” As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom through Radical Resistance, University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Feliciano-Santos, Sherina. A Contested Caribbean Indigeneity: Language, Social Practice, and Identity within Puerto Rico Taíno Activism. Rutgers University Press, 2021.

Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. Caderno n.65: Os Involuntários Da Pátria. Chão da Feira, 2017, https://chaodafeira.com/catalogo/caderno65/.

Yusoff, Kathryn. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. U. of Minnesota Press, 2018.

García Pelatti, Luis. “NULO EL REGLAMENTO CONJUNTO A LOS 100 DÍAS.” Sin Comillas, 13 Apr. 2021, https://sincomillas.com/nulo-el-reglamento-conjunto-a-los-100-dias/?fbclid=IwAR2uu36ZR0ziT1lZKf8EX0-fYffHbmpUt_divOsURf5KTe7t6wJOLjN4q9Q.

Alvarado León, Gerardo E. “Parca La Presidenta de La Junta de Planificación Sobre Críticas al Reglamento Conjunto 2020.” El Nuevo Día, 1 Oct. 2020, p. n.d.

Alvarado León, Gerardo E. “Entidades Advierten Sobre Posible Impacto Ambiental Si Se Aprueba El Reglamento Conjunto 2020 de La Junta de Planificación.” El Nuevo Día, 25 Sept. 2020, p. n.d.

Wood, Tania E., and Grizelle González. WhendeeL. Silver, SashaC. Reed, MollyA. Cavaleri, "On the Shoulders of Giants: Continuing the Legacy of Large-Scale Ecosystem Manipulation Experiments in Puerto Rico." Forests 10. no. 210: 2019. 1-18. MDPI. Web. April 19, 2021New York City Soil Survey Staff. New York City Reconnaissance Soil Survey. Staten Island, NY: United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service, 2005. Print.