The colonial subjectivation of indigenous lives always grounds itself in the redefinition of the relationship between human and land, where by land I mean the topography of living soil, bodies of water, forests, mountains, deserts, not a state defined by political borders but what eventually falls under it. Human-land relationality gets shifted by transplanting people, claiming (the absence of) proprietary rights to land, calling the local interactions with soil ineffective production, using people to exhaust land and land to exhaust people. In other words, colonialism uses the relationality of indigenous population to the land as a condition of humanhood and a condition for refusing it and continuously creates geographies where ecological and humanitarian devastation go hand in hand, leaving the responsibility for managing multiple crises on those who have been subjected to its violence.

How to take care of a depleted land? How depleted people can take care of a depleted land? And how do you do that under the conditions that separate the two from each other?

Even when the land is colonized and the people who live on it are restricted in their freedom or in the ways they could physically support it, the reparative work is already going through the practices that are not necessarily recognized as associated with or grounded in land. These practices are rooted in ancestral cosmologies of being-with land and nature but also get nourished by its contemporaries across borderlands sprouting towards other means of reconnecting to land, repairing relationality to topographies. And, perhaps, we can hear how they make exhausted landscapes bloom if we listen attentively enough.

Music as a practice of modifying landscapes is inherent to any culture or maybe even something that creates a culture and a society around it. For McKittrick, “musical expressions are fundamentally about place because they alter the soundscape”; I would say it is also about place because the noises of the surrounding become music, the music that then allows to reply through sonic and physical spatiality. In McKittrick’s work, black soundscape reshaped human geography cutting across “the hierarchical genres of human normalcy and re-presenting the ways in which black artists (sometimes but not always) embrace and/or perform the normal and change the stakes of normalcy.” The expression of sound for her is not limited to music and music making: “the art of noise is not just about listening, it is also about dancing, seeing, not listening, and (in)voluntarily listening to other people’s music; it also enhances our privacy, wards off loneliness, and simulates aloneness.” This “art of noise” that shifts music from a thing to “an activity, something that people do” is also what Small calls musicking and invites to expand the limited western notion of music that prioritizes musical works to experiences, practices, and performances of how we music. Walking and paying attention to musicking with two of them and many others, I want to register the ways sound expands topographies creating places where people can meet land and communicate with it, especially under the conditions of limited movement and settler colonialism. This piece is place-specific not because musicking to land is restricted to a particular geography but because living topographies inform the soundscape, and my ears are a bit more sensitive to the noises of the steppe and the landscape of Turkistan, Central Asia, which, hopefully, will be helpful in careful contextualization of the restorative sonic practice.

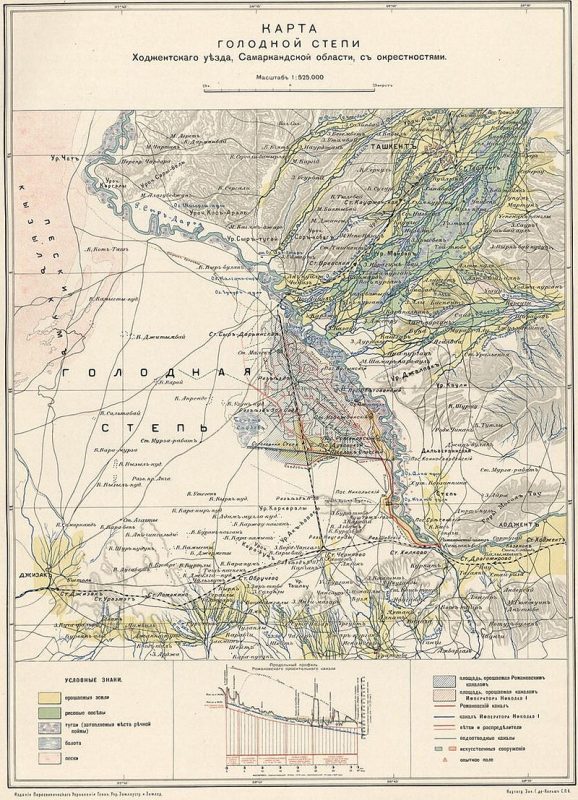

The place I am listening to was once a vast area of desert and semi-desert called Hungry Steppe that spread across the regions of Turkistan that fall within contemporary territories of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan and Tadzhikistan. “It had hot summers, cold winters, and a very short spring. During the summer months, temperatures could fluctuate radically, with high temperatures during the day and a sharp drop in temperature at night. There was generally little cloud cover, and the sun in the plateau could be unrelenting. It had very few open water sources and little rainfall. When rain did fall, it was quickly absorbed deep into the plateau’s coarse soil.” The landscape of this lowland covered with camelthorns, mugwort and saltwort was characterized by both Russian empire and USSR government as “natural”, untouched by human influence. In fact, they were looking for dramatic topographic changes and agricultural application of the soil – for the markers of sedentary lifestyle that was not suitable for those geographies. As Masanov mentioned, instead of drastic transformation of the landscape, Kazakh pastoral nomadism would adapt to the features of the steppe and its scarce water and pastureland. “Contrary to their impressions [settler colonialists], Kazakh nomads, like other pastoralists, regularly sought to change [landscape] to suit their needs. To encourage the growth of fresh grasses that their livestock could eat, they burned areas of the steppe. These fires, as well as the trampling of the steppe by pastoralists’ animal herds, helped prevent the spread of shrubs and trees. In the Hungry Steppe and other areas where there was little surface water, Kazakhs built wells deep into the steppe to tap groundwater reserves.” They did not rapidly transform the topography to accommodate the settler lifestyle. All nomadic practices entailed patience to the soil and movements to give it rest. In other words, they listened to what the steppe was telling them.

The wind of the steppe, murmur of groundwaters, hoof beats – the soundscape that Kazakh nomads called dala äuenі, steppe music, has always played a vital role in their worldview. Through noises of the landscape, they heard the state of the soil, the density of air, the direction of the wind, through steppe music they would understand how nature is feeling. The nature’s musicking happens independent from the human presence, the pastoral nomads were just very attentive listeners and learners of it. That linguistic register of steppe music was inscribed into Turkic musical instruments created from and mimicking the landscape itself and expressed the sounds and soul of the steppes and those who live there in küi, instrumental musical compositions, that would tell whole stories without using a single word. Küi would narrate for seasonal changes, migrations of animals and humans, childhood memories and deathbed regrets, folk heroes and separated lovers, it would replace words when you had to announce good or bad news. Küi is not a solitary practice, but it does not require human listeners; its primary audience is nature. Therefore, if Kofi Agawu would ask what steppe music is incomplete without, the answer would be land, steppe itself. Humans are secondary to it. In this sense, musicking of land and people was an invisible emotional connection and never-ending conversation, that went beyond the practice of music. When you are attuned to hear land’s musicking, it means that whatever you do in relation to it becomes musicking too. Riding a horse through the steppe, fixing your yurt in its soil, running barefoot as a child, splashing hot drops while milking on a chilly sunrise. And even a nomadic body put to overwork its soil and to deplete its waters was also attuned to the land, but, in this case, to its song of sorrow.

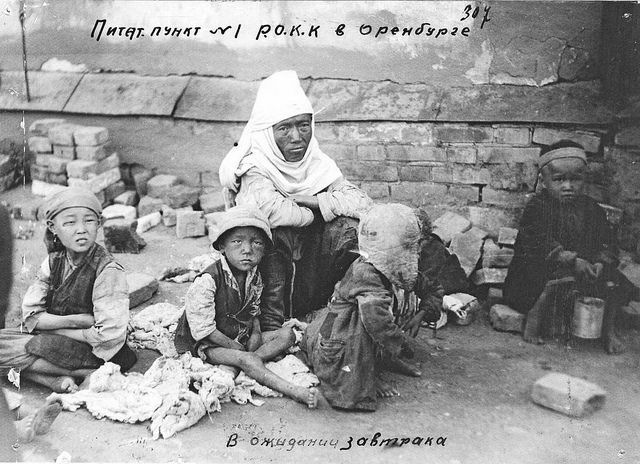

Pastoral nomads musicked to the land through soundscape and movements according to its rhythms – the seasonal and natural changes – and by accessing the resources of the landscape without vitally disturbing its ecology. This relationship was viewed by settler colonialists as ineffective use of the territory. Therefore, with the expansion of the Russian empire across the region that later turned into the USSR, the reclamation of the land, as well as major irrigation projects of redirecting rivers across formerly natural semi-desert areas, became central to the transformation of Central Asia into an agricultural and natural resources supplier of Moscow, while turning forcefully settled nomads into the workforce under the constant pressure of unreasonable production scale. The USSR government would request an unrealistically high amount of harvest even during dry seasons, pushing the overuse of the soil and human labor, while collecting all the produce and criminalizing workers who tried to get some food for their families. In addition to that, Moscow requested large numbers of livestock that were continually getting weaker and dying under forced sedentary conditions and restricted pastures of exhausted soil and no fresh grass for animals. “By forcing rural people to give up their land and livestock and enter collective farms, Moscow sought to tighten control over the food supply and boost the Soviet Union’s production of meat and grain, particularly wheat.” The politics of collectivization that has started from drastic landscape and lifestyle changes led to ecological and humanitarian crises in the region. The loss of livestock, refusal of access to agricultural products made by their exhaustive labor brought great hunger that took the lives of around 3 million Kazakhs and made one-six of the indigenous population who had a chance to run away leave their homeland forever. What used to be a hungry steppe geographically became a hungry steppe of people.

Yet the cry of the land and the people was muted. The horrors of Kazakh famine were presented as “miscalculations”, “misunderstanding of cultures”, “inevitable outgrowth of modernity” that came from transformation into settled lifestyle and not an active act of violence from Moscow—”or at least not as violent as Stalinist crimes committed against settled societies.” The responsibility for “administrative mistakes” has partially fallen upon Goloshchyokin, the party representative who conducted the Small October policy in Kazakh SSR, but no one was held accountable for the horrors of the famine and the topic has been prohibited from the discussion. Even after the Soviet Union collapsed, the Great Hunger of 1931-32 has not been widely researched and acknowledged like Ukrainian Genocide from collectivization. Only in the recent decade it started appearing as a part of national trauma and tragedy, but if we listen close enough, we can hear the cry in the music way earlier, even when the words were censored.

Betpak Dala – translated as Ill-Fated Steppe – is a northern part of Hungry Steppe, as well as the opening song and the name of 1976 album by Dos-Mukasan, a vocal-instrumental ensemble from Alma-Ata, sometimes referred to as Kazakh “Beetles”. They started as an amateur student band, gained professional status winning major Soviet and international awards, and released several singles and albums under the only USSR record label “Melodia” which at that time both signaled popularity within Soviet republics and being under the constant inspection of the party. That meant that the repertoire of the ensemble and the presentation had to be approved by the party. This censorship can be read even in the tone of the liner notes to the record that describes Betpak Dala song composed by Murat Kusainov as “a dedication to the reclamation of boundless lands of Kazakhstan.” This is the only composition on the album that was accompanied by such explanation for several reasons. First of all, other songs were either covers of Kazakh folk songs or their textual content was quite apparent and non-problematic for the communist party, while Betpak Dala, a 7:47 minutes long psychedelic instrumental play, not only was unexpected for their previous repertoire but also worked within the genre uncommon for Soviet music estrade and was largely criticized for its western roots in capitalistic states, popularization of drugs, nihilism and stylistic non-conformity. The fact that it was even approved for a recording is surprising. Perhaps, it was “given a pass” due to the “ethnic” component of Kazakh musical tradition or the absence of lyrics that could be interpreted as dangerous. The reasons why it was allowed by the Soviet Ministry of Culture is definitely speculation that even the ensemble itself could not understand: as Arsen Bayanov, their drummer during that time, phrased it: “I can only assume that the system already started to glitch.” All of these make you read the description in the linear notes a bit more carefully: it makes one understand that this song, which was “definitely not loyal to the Soviet regime, but rather hostile”, was a risky pass that had to be defined within the terms of the party praise. I am also arguing that Betpak Dala re-created the soundscape of suffering Hungry Steppe reconnecting to the land through musicking that Moscow’s ears could not register just the way their eyes have labeled insignificant the nomadic relationship with the landscape. Yet I am not trying to reduce the virtuosity of the piece that, at last, has been gaining a deserved recognition as a simultaneous origin and death of psychedelic rock in the USSR, to a mere decolonial reading; what I want to say here is that Dos-Mukasan as a collective phenomenon of its time through an attentive exploration of the soundscape transformation was able to translate the topographic changes of life and death. They let music absorb the cracks and stains of the soil, breathe in mugwort and industrial dust, catch the rhythm of movement in and out of synch with the land. As Omaruly wrote after hearing them live: “Later I realized: they didn’t just perform songs, they researched, studied music.”

I invite you to attune to reparative sonic topographies of Betpak Dala that were mapped by steppe music, psychedelics, the youth, and the collectivity in the 60-70th Alma-Ata noises that brought together ancestral traumas, communist ideologies, and national reimagination, feeding cultural hunger of the generation nourished and protected by their famine-survivor parents.

Intermission

We are on a short intermission after the first program of Dos-Mukasan’s concert satisfied by hearing our favorite classics “Toi jyry”, “Almaty tünі” and others from the familiar festive and soothing repertoire that elevated the ensemble from an amateur student band to professional recognition in a short period from 1967 to 1974. These are the songs premiered in the warmth of Alma-Ata nights when Polytech students new to the city from their aul would gather with guitars, contraband rock records, and cheap portyuha; the songs composed with the excitement about the first wedding in the friends’ group on a train headed there; the songs performed in front of 20-thousand participants of the X World Festival of Youth and Students including Angela Davis, Nicolás Guillén, Valentina Tereshkova and others who visioned liberation across borders. Yet they sounded more mature in today’s performance, perhaps, reminiscent of the times when freshman Dos, the only one with any musical education, would teach his friends Murat, Khamit, and Meir how to play musical instruments to impress their female classmates; in few years they were relocated to build roads in the same sovkhoz with Hungarian students, who jammed with them and advised to start a band called Dos-Mukasan from a combination of their names. But even though their student days are far away now, we could still feel samal, a pleasant cool wind, spreading from their music. Samal that, as a student-organized club, advocated for a spacious room where Polytech students could come together, invite artists and thinkers, and have heated discussions preventing math students from becoming “dry” tech professionals. Samal that would move Dos-Mukasan’s music-making and the souls dancing with them. Of course, the ensemble has changed. Even though they have gained international recognition, for the members who are pursuing their doctoral degrees and political service musical career is not the priority, but music is. So, they still come together, embrace new musicians from their alma mater, rehearse for months, and tour way beyond the USSR. I’ve heard, they just came back from touring in Caribbean countries and the USA.

Well, it is time to get to our seats, the second program is about to start. Soviet concert hall etiquette is strict: no tardiness, no noise, no movement is acceptable. The lights go on and an organized clapping welcomes the ensemble back. The claps go silent taken over by whispers when Dos-Mukasan comes back changing their costumes with national ornaments into jeans and undershirts. Something they’ve picked up in the West? We don’t get to discuss it as the bass guitar boldly takes over the soundscape. Maybe, we can have some tea afterward.

Betpak Dala

I am going to give you a minute here in case you want to get your headphones and read with Betpak Dala. (In case, you have decided to music with reading, please, do not try to follow the footnotes. Consider, coming back to them later.)

The bass guitar softly and confidently steps into the yet-to-be-seen landscape setting up the base of the piece. It is grounding the listeners, letting us reconfigure our body because we are about to walk a lot, to walk far. As we are making our cautious baby steps percussion drops resonate giving directions within the soundscape: some come from afar as metal clanging on a distant traveler’s luggage, some fall on us as a droplet making us look at the sky, while another droplet goes deep splashing the groundwaters and making us realize there is a whole dimension beneath us that we must be aware of. Percussion prepares us to listen to the landscape.

Betpak Dala is the land we entered.

Now that we know where we are, we need to adapt to the steppe topography. We let fellow travelers help us get on a horse because the journey is long, and we are just a human part of it. The companions are attentive to the surrounding and to us within it: their pace is hasteless, they won’t let us stop or fall behind giving chances to get in synch with the rhythm of movement. It is a speed of nomadic companionship that doesn’t outrace the ones you travel with: as long as we are in motion together, we are the closest people, zholdastar, who rely on and take care of each other. “We will not necessarily reach the same place, and many of us will not even reach any recognizable place, but we share the same starting point, and that’s enough. We are not all headed to the same address, but we believe we can walk together for a very long time.” What feels like needs to be a longer synchronized movement within the life that used to be nomadic and within this instrumental play methodically shrinks via layering up high synthesizer cords that fluctuate the soundscape and deform the landscape we were just getting used to.

The lead guitar strikes with its entrance overlapping the pace set by the bass. Maintaining the tempo that we have adapted to becomes increasingly hard, so we try to get in synch with the lead guitar’s rhythm, but it keeps distancing itself from us, making us always fall half a step behind. The lead guitar just saw the landscape for the first time but is already convinced that the pace of the bass is too slow to make it sound progressive. Modernity cannot wait. Try to catch up with its speed for now and come back to the text after the song ends.

We’ve departed during the intense sonic experience of Arsen Bayanov’s drum solo that followed by Murat Kusainov’s bass guitar set the song off to its inexhaustible virtuosic groove, which could go up to 15-20 minutes during live performances. According to Bayanov, studying the sound of drum-bass interaction they developed the rhythm that was a prelude to Kusainov’s composition Betpak Dala, further layered up by other musicians of the band. Due to the expression of psychedelic as a genre and lifestyle, the band’s drug use was speculation that Bayanov refutes 50 years later claiming they had no access to psychedelics but plenty of port wine. Their groove could have been a moment of ovation and fan cheering and could have defined the ensemble’s direction and popularity somewhere outside the USSR but Soviet concert musicking had strict protocols where vocal and physical indulging in the music was under limitations even for the performing artists. Yet, with or without drugs or dancing the composition takes a listener for a trip, the topography of which I found important to introduce. I think because of the initial methodical grounding through the soundscape and the rhythmic spatial movement at the beginning of the song the listeners keep their attachment to the land even when the rest of the composition might seem disorienting. But this time, with the speed-up and layering-up of noises, we are not walking in space, we are traveling in time through the changes around. Instead of letting us go with it, the pace revolves and intensifies around us, settling us in a position where we can observe things happening in the landscape but not participate in it. Staying grounded we watch the heavy machinery dive into the soil, we hear animals in distress, we feel the speed with which disoriented people flee their homes. This feels simultaneously like a perspective of the land itself during the process of transformation and a position of someone able to hear and understand that story, which is what psychedelics might help with by expanding consciousness but here instead of drugs they used land and its soundscape.

Electronic musical instruments helped Dos-Mukasan to express the changed voice of the land that had already gone through the agrarian and industrial transformations, where the steppe music, küi, attuned to the landscape that has not been reconceptualized through modernity became not enough to music the rapid invasion of technology to the soil. Dos-Mukasan were among the pioneers of electronic musical instruments within the Kazakh estrade. The influence of Western rock-n-roll was never denied, they made covers of international hits without the knowledge of languages except for Kazakh and Russian but being fluent in instrumental language. When it came to Kazakh folk songs or their original compositions electronic sound was not an attempt to “westernize” national music. They carefully interweaved it into the transformed Kazakh topographic experience that can be felt in Betpak Dala. I think what electronic guitars and synthesizer give here is the speed enhanced by the aftersound that allows to soundmap the persistence and heaviness of landscape alterations and their durational effects.

In my listening, Dos-Mukasan are theorizing positionality within a rapidly modernizing landscape and creating conditions for others to think with them. Their study of music and the study of how to music was not a quick revelation but rather an evolving collective process that I cannot separate from their student life. Most of them grew up in a village taking care of livestock and crops and learning how to communicate to land before moving to the city where they learned how to use land and its resources as engineers, so, they were already experiencing how the language and methodology of productivity changed the landscape. Further obligatory summer labor on constructions where they have built physical roads and connections to students from other Soviet republics expanded their interaction with land modification, borders, belongingness and developed their artistic repertoire. And, of course, Samal student club as the place for gathering they have created themselves, where they could think, talk, music, and dance together. As paragraph four of the club said: “All members of the club can wholeheartedly have fun, sing and dance at our evenings. And the Dos-Mukasan quartet will play whatever you ask for. “ Therefore, their audience was music-making with them all the time. But there is also something else here. As a generation whose parents were born during or right after the famine and collectivization, they have been raised with the horrors of hunger in recent collective memory. Yet if for their ancestors at a certain point it might have been unclear how to address the violence of settler-colonial policies, this generation of 60-70th became fluent in the language of the party and industrialization and knew the registers they needed to sing, talk, act back to build better living for their community. As Gandelsman, the dean of their department, surprised by their rigor to pursue non-academic activities and community-building, has said, “the students are full owners of their dorms and do everything on their own initiative.” I think this feeling of the capability to navigate even within institutional spaces comes from the attunement of the band and their contemporaries to the topographic changes that brought them to their positionality and to the adaptation of the new methods of connecting to land and to musicking with it.

Santos, Boaventura de Sousa. 2014. Epistemologies of the South. London and New York: Routledge,From Kazakh, zholdas is a companion on a long journey / someone you closely share a social environment with / a romantic partner / a close friend / a thing you have an inseparable bond with

Zhukov, F.. January 25. "Samal - svejiy veterok." -, 1969.Kazakh Polytechnic Institute (KazPTI), the strongest engineering school in KazakhSSR where outstanding students from all over the country who passed state exams with the highest science scores would come together. It was an alma mater for scientists and intellectuals who took the development of KazakhSSR into their hands, significantly reducing the influence of the party governors from Moscow.

Agawu, Kofi. 2016. The African Imagination in Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press, Omaruly, Karjaubai. "Ansambl "Dos-Mukasan"." Leninshyl jas, 24 Feb 1971. Bayanov, Arsen. "Betpak Dala - Istoriya odnoy plastinki." Argumenty i fakty, 2 May 2021. Accessed https://kzaif.kz/culture/betpak_dala_istoriya_odnoy_plastinki_plastinki_2. Melody "Dos-Mukasan." Accessed 2 May 2021. https://melody.su/catalog/estrade/44310/.I wish I could go in-depth into how different instruments emerged from the living topography of Eurasian steppes and became an orchestra of its feelings, but that would be a slightly different project. The landscape I’m listening to has already been marked and stained by settler colonialism and the musicking transformed with it.

“Dala” that used to mean steppe, open land, homeland and the habitat for nomadic Kazakhs, with sedentary colonialism started to signify the outside of a house and is also used to juxtapose village to city.

Suslov, S.P.. 1961. The Physical Geography of Asiatic Russia. Translated by Noah D. Gershevsky. San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Co, Cameron, Sarah. 2018. The Hungry Steppe: Famine, Violence, and the Making of Soviet Kazakhstan.. ITHACA; LONDON: Cornell University Press, Masanov, Nurbulat. 1995. Kochevaia tsivilizatsiia kazakhov. Almaty: Socinvest, Small, Christopher. 1998. "Music and Musicking" Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. 1-19. Middletown, Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, McKittrick, Katherine. 2006. Demonic Grounds: Black Women And The Cartographies Of Struggle. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,